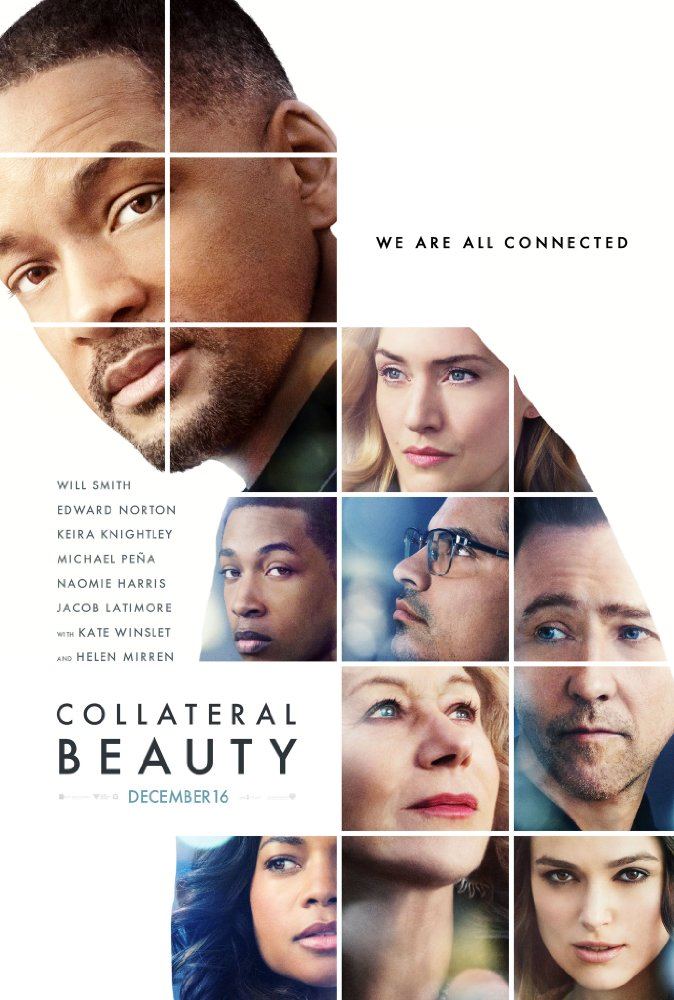

To say Collateral Beauty, Hollywood’s latest star-studded holiday-season film, isn’t a good movie is to give the film the benefit of the doubt. It’s to assume, reasonably, that the film was meant to reach depths of emotion, to inspire you to hurt deeply and love bravely despite it, wrapping those lessons in a heartfelt story and finishing with an unexpected plot-twist, the bow on top of the present.

To say Collateral Beauty isn’t a good movie is also to be kind. Indeed, it’s an awfully bad movie for anyone who has seen enough movies to recognize its uninspired clichés, lazy plot clues, and thinly-veiled emotional manipulation. Without that benefit of the doubt though, it seems clear the movie didn’t attempt very lofty goals at all; it couldn’t have actually tried and have missed so badly. Instead, Collateral Beauty seemingly aspires to be blatant grief voyeurism, the kind to which, if a film is lucky, finds a cult following from teenagers who find it beautifully deep as the rest of us do our best not to sleep, seethe, or vomit. An exception to Collateral Beauty’s mediocrity is Helen Mirren, who was comedic in half her scenes, charming in the other half, and endearing in all of them.

The concept of the film is faithful to its trailer; very faithful, as there little more added than what you learned and could have predicted from a 30-second synopsis. “What is your why?” successful marketing executive Howard Inlet, played by Will Smith, asks during a company-wide meeting in the film’s opening. “The big why – why you are here?” He introduces the concept that is to be the staple of the film, that we live for three basic concepts the govern our behavior, the 3 abstractions of love, time, and death.

The concept itself feels reminiscent of A Christmas Carol, which, for its time, was obviously so influential and moving as to become cliché long ago. In that sense, the story of Collateral Beauty, its protagonist’s loss and his spiritual intervention to urge him to seize life again, is simply a story for the wrong century. Or, as I came to learn, a story for a certain age. In my own twist of fate, I actually screened Collateral Beauty with a bunch of teenagers. They were about 13 to 15, mostly girls, black and brown, having the type of fun at a movie you can only have as teenager who don’t spend much time out at movies. As it turned out, watching them watch the film was better than the film itself, as their experience of such a grossly trite film was nothing short of astounding. Clichés, to them, weren’t clichés yet. They could listen to Edward Norton say to Keira Knightly, with a straight face, how “I didn’t feel love, I had become love,” and not wretch.

My entire view of the movie changed when I applied the standard of a YA novel to the film, which is where I think it belongs. It was a disastrous domino effect: Collateral Beauty didn’t need to be a terrible film, but it had the wrong target audience, causing it to have the wrong cast, causing a hackneyed script to provoke a gag reflex in adults who wasted their money. But as a teen movie? Replace Will Smith with Willow and have her lose a best friend instead of a child, and suddenly the film fits its standards perfectly. Suddenly “nothing’s ever really dead if you look at it right” seems less a ridiculous line than a mature observation from a young person figuring out the world. Suddenly “your children don’t have to come from you, they go through you” is given the same benefit of the doubt you afford a teen movie.

A domino metaphor is used throughout Collateral Beauty to a certain effect – to convey the beauty is in creating something, losing it, and starting all over again. And perhaps that’s true for movies like this: that while, to us, they are painfully cliché exhibitions of grief porn, to a YA audience it actually lands. After the movie’s final reveal and the credits began to roll, the girls in front of me were allowed to react in earnest. “I never thought of that!” one girl said. “Oh my god,” from another, and “Wow. That was such a good movie, sis.” Most of us wouldn’t agree. Collateral Beauty is not a good movie. You will likely find it terrible. I don’t recommend you see it. But scripts like this one surely have their place, and to a young audience it offers the chance for newer moviegoers to become familiar with old themes in new, relatable ways. It just wasn’t done here, and so most viewers will suffer.

Are you following Black Nerd Problems on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr or Google+?

Show Comments