On September 30, 2016, I was excitedly looking forward to discussing Luke Cage and its many allusions to hip hop, which included Notorious B.I.G.’s portrait, Method Man trading hoodies with Luke, and each of the episodes bearing the titles of Gang Starr songs. I was feeling it like I was in the bodega with Method Man and about to rush him for the bullethole-filled hoodie. Of course, my students stared at me as I dared them to get excited too, which is what most students do these days until they watch it and see that I am not telling them to watch the sleepiest, most convoluted show possible. So, before I went back to talk to them on Tuesday morning, I devoured all 13 episodes.

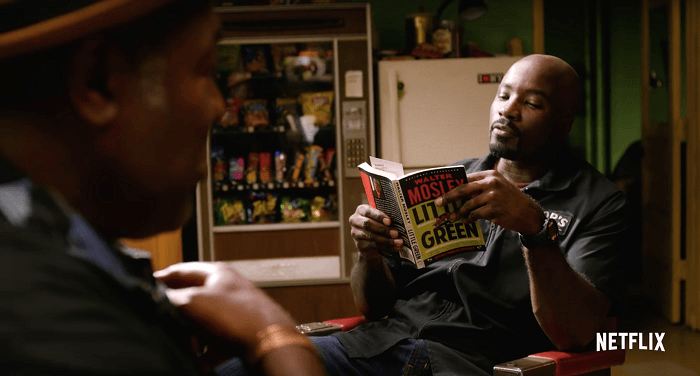

The hip hop allusions and appearances were crushing my entire heart — the opening sample of the Ghetto Brothers; appearances from Faith Evans, Dapper Dan, Fab 5 Freddy, and Jidenna; paraphrasing B.I.G.’s “Ten Crack Commandments;” when Luke calls two thugs “Plug One and Plug Two” like De La Soul; Misty Knight referencing Raekwon’s “Ice Cream” and Mobb Deep’s “Shook Ones” in a particularly poignant monologue; and Method Man chopping it up with Sway and Heather B. My two obsessions entwined on this show — hip hop and books. Books are such a significant part of the dialogue in key scenes, and how often does any show feature a Black man with an affinity for books — as any character, much less the lead?

The books on Luke Cage’s bed in episode 1: Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers, a book by Julius Lester — a collector of Black folklore, and Attica by the New York State Special Commission on Attica. In this quick scan of books, the first-time viewer sees Luke’s love of history and literature pop out on the screen. On display is his deep understanding of Black life and masculinity, and what it means to be someone who can shift things from the periphery to the center, even if they are incarcerated, is paralleled by those books.

Acres of Skin: Human Experiments at Holmesburg Prison by Allen M. Hornblum

Luke Cage’s beginnings as a scientific experiment are not too far from the truth, especially since his power resides in his skin. Acres of Skin discusses the history of medical experiments on Black prisoners that helped make skin grafts possible. A more recent book that chronicles medical experiments on Black people throughout America’s history is Harriet A. Washington’s Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present.

Cutting Along the Color Line: Black Barbers and Barber Shops in America by Quincy T. Mills.

The history of Black barber shops as a gathering place is not surprising, and when people congregate and share ideas in Pop’s Barber Shop or metaphorically refer to his spot as “Switzerland,” Mills’ book offers some insight into why barber shops are about more than cutting hair.

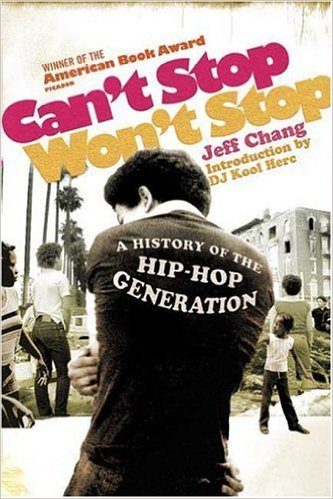

Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop by Jeff Chang

If you don’t get the hip hop references, Jeff Chang’s survey history of hip hop’s beginnings will probably help, but it also talks about the concept of “benign neglect” and how public policy, politics, and social conditions helped create hip hop. One of the key players in that scenario is Robert Moses. For more on him, there’s Robert A. Caro’s The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York.

Free Stylin’: How Hip Hop Changed the Fashion Industry by Elena Romero

At this point, hip hop has left its mark on fashion. The documentary Fresh Dressed shows how hip hop artists invented their own fashions out of necessity and have become trendsetters in elite circles. Free Stylin’ is the scholarly take on how hip hop changed fashion.

Fist Stick Knife Gun: A Personal History of Violence by Geoffrey Canada

In one scene, Cottonmouth Stokes mocks his cousin Mariah for wanting to go “the Geoffrey Canada route.” Canada is best known for his book Fist Stick Knife Gun and founding Harlem Children’s Zone. Another book about Canada and his work is Whatever It Takes: Geoffrey Canada’s Quest to Change Harlem and America by Paul Tough.

Where’s Waldo? by Martin Handford

Since Misty Knight visualizes the logistics of every crime scene through photographs, she explains how she was always the fastest at finding Waldo as a kid. This is the only children’s book mentioned.

Playing the Numbers: Gambling in Harlem between the Wars by Shane White

Wealth-building in Harlem was also part of an underground economy that allowed some Black business owners to support local artists, athletes, and other businesses, even if they ran numbers, prostitution rings, prohibition-era night clubs, and racketeering in movies like Hoodlum or The Cotton Club. There are other history books that, like this one, mention Stephanie St. Clair, a woman very much like Mama Mabel in Luke Cage. Another book worth reading next to this one could be Harlem: The Unmaking of a Ghetto by Camilo José Vergara.

Diamondback, one of Luke Cage’s adversaries, touts The 48 Laws of Power and carries around a heavily annotated edition of the Bible that his mother gave him.

Negroes and The Gun: The Black Tradition of Arms by Nicholas Johnson

Another nod to Diamondback is when he insists to Mariah Dillard that the history of guns in America is built on creating fear towards Black people after Reconstruction, when the Ku Klux Klan rose to prominence and Jim Crow began to thrive. Johnson’s book not only relates to Diamondback’s point, but also reveals the tension between self-defense, politically radical violence, and the nonviolent practices of the Civil Rights era.

In the last episode, Luke is holding a copy of The Heat’s On by Chester Himes. Luke also mentions Michael Connelly, author of the 21 existing Harry Bosch novels.

There so many allusions and references sprinkled through this thirteen hours of television. Add any I may have missed, or that you think are required reading, in the comments or on Twitter with the #LukeCageSyllabus tag, so we can find it.

Are you following Black Nerd Problems on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr or Google+?

Show Comments