[divider type=”space_thin”]

I tried, y’all. I really really tried. I started watching Detroit twice — once at the movie theater and once on an uncle’s bootleg when that failed. Never finished it. It felt wrong. Like eating collard greens from anybody other than the aunt who really knows how to cook them. It was a violence.

How can I put this…

[check_list]

- #BigelowDetroit pulled up in its earth-conscious, eco-friendly sedan, parked in year already full of people and history and stories and started re-naming everything because it was undervalued.

- #BigelowDetroit moved to Detroit but it felt “gritty” and “real” and started a microbrewery soon after with a flagship beer called “’67 Riot” to honor the unspoken history of the city.

- #BigelowDetroit suffixed the name of her new business “Detroit”, supplying a service she alone deemed as a need and necessary, while stationing its foundation in a nearby suburb.

[/check_list]

Look fam: there is something sadist in the obligation to give hours of your time over to something in the name of being seen as reasonable or fair, of being painstakingly careful with getting it right. Especially when that entity seemingly never cared enough about you, its audience or the work to do the same. And listen, I understand professionalism and objectivity and… stuff. I do. But given the subject and its personal connection to not only myself but family, friends, elders and residents I deeply respect, I can say with no hesitation that there’s limits to those mercies.

There’s been plenty of absolutely fire reviews detailing everything from the film’s questionable rollout/premiere in its namesake (Jamon Jordan) to why the movie leans more into exploitation than storytelling (Danielle Eliska Lyle/Metro Times, Richard Brody/New Yorker)— all of which I agree with. I live in Detroit 24/7. I didn’t need to finish Detroit to know exactly what it was. Living inside my city, especially in its current climate, I know all too well what the gentrification and selective erasure of stories feels like, even before having to get to the part where they rename some part of my history.

I’ve sat through every one of the Fantastic Four and X-Men movies, breh. I can identify the symptoms early when somebody is taking an entire canon known, analyzed and respected dearly and getting it pretty damn wrong.

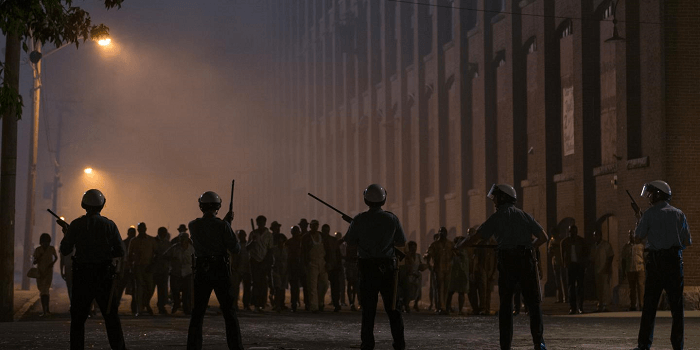

Watching Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty showed me Kathryn Bigelow’s tendency to depict militarized authoritarian forces as The Avengers, validating the injection of their heavy-handed presence and sometimes toxic behaviors into spaces by romanticizing the threat they faced. I believe ultimately it’s wielded as a mechanism to dissect hyper-masculinity in war but there’s times when that motive is lost completely in her work. Go Drake / “Back to Back” on Zero Dark Thirty and Age Of Ultron in a double-header and tell me I’m wrong.

I warned how wary I was about her particular approach being attached to the ’67 rebellion months ago and between what I did see and what I’ve been told by many of my peers, that concern was validated.

For me, it’s not just the use of a white director and white writers spinning a story centering historical black trauma simply because the story “needed to be told”, but moreso who exactly it was helming it. I knew Bigelow would nail the aesthetic of everything— the sound, the emotionally-appropriate lighting, the raw torque of what the inside of the Algiers Motel that night in 1967 probably felt like. From Point Break or Hurt Locker that has been her wheelhouse. But I knew how it usually came at the expense of some fuller, greater story being overlooked.

More research by Bigelow [and writer Mark Boal], more engagement with powerful existing work surrounding the ‘67 rebellion (Dominique Morriseau’s Detroit ’67 play, John Hershey’s book Algiers Motel Incident, the documentary 12th and Clairmount, etc.), more conversations with some of the residents near the Algiers and historians here in the city who have pined and combed through the ’67 rebellion decades before this year’s anniversary run, more preemptive concern with getting the story right rather than out, all would’ve shaped the film to be a more accurate depiction of its namesake.

And the absence of black women from an experience this charged and collective is simply inexcusable. Rebecca Pollard, Viola Temple and Margret Gill (the mothers of Aubrey Pollard, Fred Temple and Carl Cooper— the 3 black men killed inside the Algiers that night,) and Mary Jarrett Jackson (Detroit’s crime lab chief who examined their bodies, was key in prosecuting the police involved and key perspective from within the racist police department) are just two examples of why that particular absence is glaring and completely avoidable.

These are just some of the reasons the film has been called a “moral failure.”

Yes, Bigelow certainly succeeds at triggering deep wells of paralyzing white guilt, and that gut punch in this Trumpian America is vital. But doing so while mining a city’s pain, recklessly whiffing on a more robust narrative around the triggering subject, and naming your movie eponymously after the city you primarily did not shoot in or source valuable historical accounts from negates whatever benefits are found.

#BigelowDetroit saw a story that they felt the world needed to hear no matter what, but with an already complex and harrowing history, that approach becomes the exact problem.

Are you following Black Nerd Problems on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Tumblr or Google+?

Show Comments