The typical single-issue American comic that you can get from your LCS is roughly 6 by 10.25 inches. The story content sans advertisements, front matter, and back matter will typically consist of 20 pages, however any multiple of four is generally considered acceptable given how production works. Of course, this is “industry standard,” more convention than hard fast rules that must be followed at all costs. For example, DC Comics’s Black Label released Joker: Killer Smile, which measures at 8.5 by 11 inches. All of this to say when you’re reading a comic designed for print, they are known constraints, rules that dictate what you are readily and easily able to do. The literal canvas the artist and writer have to work with is finite.

But that’s only when you’re dealing with print.

The Digital Landscape

For the longest time, I have been fascinated by the concept of the “infinite canvas.” This is a term that Scott McCloud coined in his 2000 book, Reinventing Comics, the spiritual successor to the beloved Understanding Comics. It’s a very simple concept: when you’re online you are not bound by the borders of the page. With the ability to scroll and zoom in, creators are granted virtually infinite amount of space to work with. McCloud himself experimented with this format with his story The Right Number, when the next panel was embedded at the center of the current panel. As you clicked through, you’d zoom in to continue the story.

The format and the concept itself did not catch fire as McCloud predicted. Comics still mostly exist as panels and strips, and to fundamentally alter the experience is very analogous to going from PowerPoint to Prezi. And for those unfamiliar with office presentations tools, you’re going from a linear sequence of information to a modular, user-defined structure. Which is to say, the person creating the presentation/comic is doing a lot more work and pre-planning to fully leverage the self-created infinite space.

But even if the full potential of the infinite canvas has not been fully realized the fact remains that when you look at digital comics, there is a utilization of space that is hard (and sometimes impossible) to replicate in print.

Digital Readers

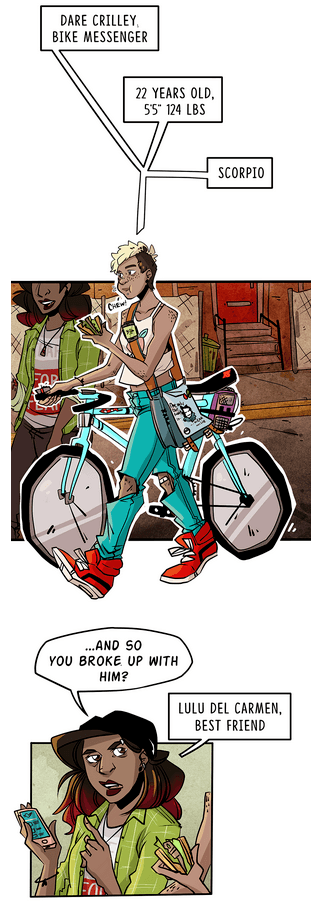

As a mentioned the last time I talked about webcomics, I’ve started reading a couple comics on Webtoon. My main interest is a strip called Messenger, and what’s truly fascinating about the Webtoon format is that while it resembles a conventional strip, the format is optimized for mobile scrolling. There is no pagination, each chapter is just one very long vertical strip of comic that hypothetically could be strung together to create a sort of infinite scroll experience. It’s a very different experience reading from a PDF or VIZ’s manga app, but it still a comic and shows what happens when you alter the limitation of the canvas.

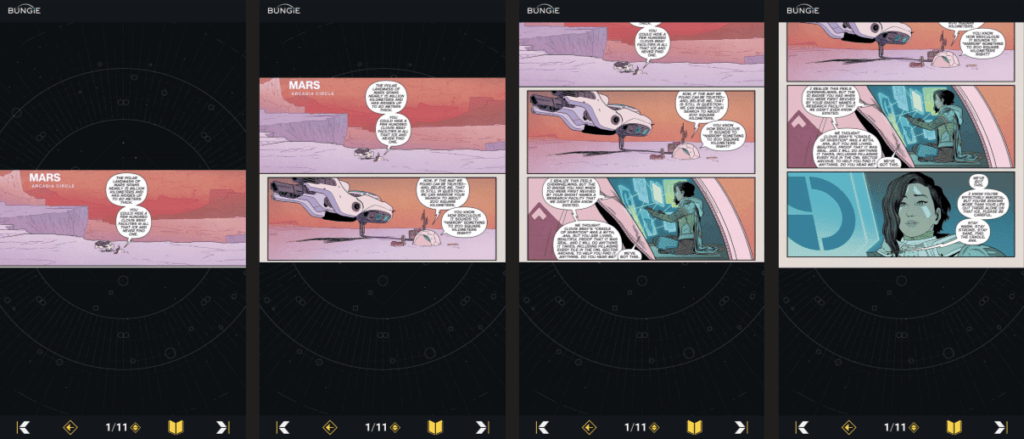

And other digital readers also manage to play with the conventions of printed page. If you go to Bungie’s comic book reader on mobile, rather than present each page, the reader works on a single tap interface that progresses the story panel by panel. It controls the information, allows you to appreciate each scene by itself and in the larger context, and gives you a chance to look at specific details in those scenes. It’s a simple change from the desktop page by page read but shows how the experience is capable of changing between mediums.

Utilization of Space

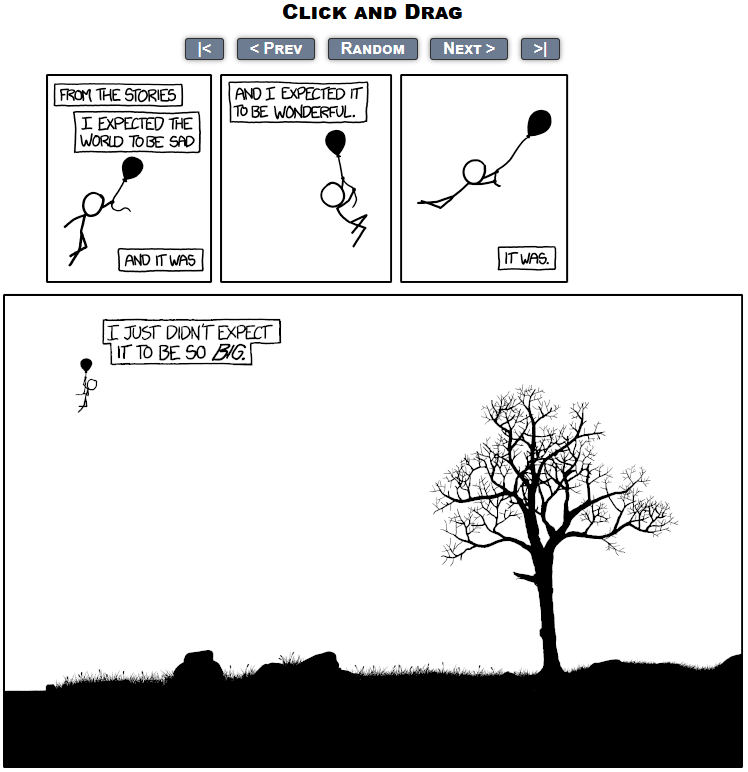

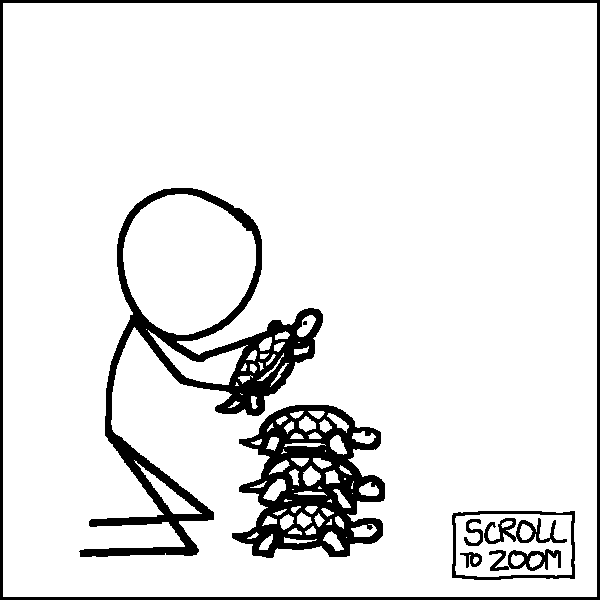

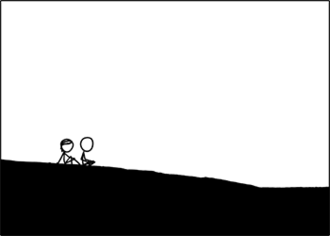

Webcomics’s access to the infinite canvas lets them tell stories and jokes in ways that physical comics just can’t. My three favorite examples from xkcd, where the ability to click & drag, zoom, and update a single panel over days. This provides a sense of exploration and discovery that’s unique to webcomic.

Homestuck famously incorporated animation, video, HTML5 games, and music into its gargantuan tale.

And even if it is something that’s replicable in print, Rich Burlew’s Order of the Stick literally broke his typical strip convention as a visual gag to emphasis the magnitude of the event.

The authors here approach the infinite canvas, and while they don’t fully embrace constantly, they utilize the concept in a way that’s inspiring and admirable.

What’ll Happen In Another 20 Years?

I don’t know the future of comics, either printed or digital. I think they will co-evolve and mimic each other in some ways and diverge in others. There is a place for both, because they generate different experiences, appeal to different people, and lets creators choose the medium they’re most comfortable with. I’ll be going to local comic shops every week like clockwork and reading my webcomics daily, looking how the different canvas stretch to the imagination.

Want to get Black Nerd Problems updates sent directly to you? Sign up here!

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram!

Show Comments