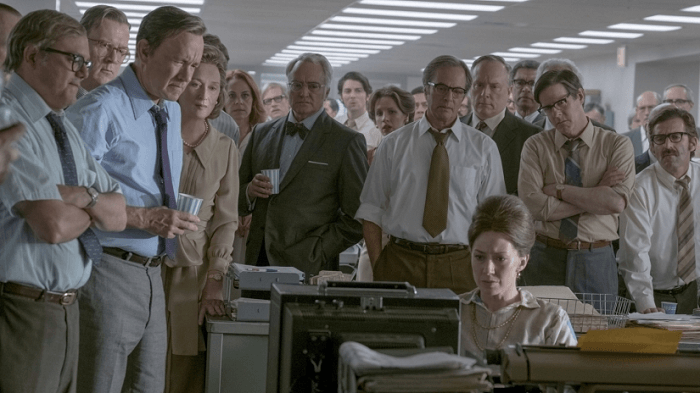

From its cast of Academy Award winners to their dramatic scenes of powerful men, clustered in a room smoke-filled room, colors unbuttoned and sleeves rolled to their elbows, The Post was made to be an Oscar darling. It’s almost distracting, even, the number of stars spread throughout the film, beyond Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks, so numerous that even the extras include faces you can recognize or plainly name for their own leading and supporting roles across television and film. It’s no wonder the Steven Spielberg-directed film attracted such talent despite the turnaround of this project – it’s said that he first read the script just early this year and committed himself to finishing the full project for a 2017 release – due to the obvious-but-unspoken connection to modern times since the election and inauguration of President Donald Trump. The Post is about moral authority against the spread of tyrannical power; freedom of the press versus the government’s ability to squelch it. The unsung hero of this film’s success is its timeliness, the year 2017.

What follows then is a film whose relevance adds a type of tension that the film itself can barely create being that we all know the result: The Pentagon Papers were indeed published and the Vietnam war is over. No one’s life is threatened nor stands on the cliff of losing everything they worked to earn (though Streep’s character is close enough to the latter). Rather, the tension comes from the underlying protagonist we can call “moral courage” or simply “the right thing to do,” implying that if it wins in 1971 the press can similarly win against a political climate we defeated before and hoped was no more. In that sense, watching The Post feels less an escape into the movies than watching a spectator sport where you wagered your house on the outcome. You know the outcome, but you still feel a tingle when you watch it on ESPN Classic, knowing what might have been, what could be.

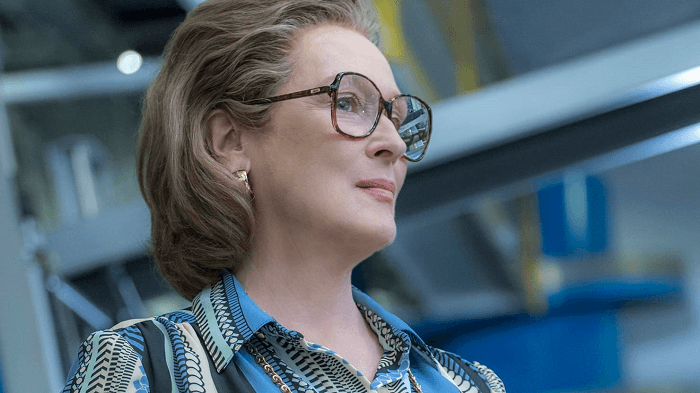

Meryl Streep plays Katharine Graham, the publisher of The Washington Post. She has the most to lose, though having inherited the company that no one expected her to have, including herself. Her character is one of insecurity, her knowledgeability quelled under the weight of outspoken and numerous men, being the only woman in a boardroom. Streep’s performance is one of quirks and ticks and mumbles, capturing the self-doubt of someone pushed into leadership without having been asked, before they feel comfortable, confident, or ready. You have the sense from the very beginning that she is the reluctant decider, the woman who will take the final shot of brave triumph. She begins lily-livered only for you to cheer for her building confidence, a sureness of herself that she deserves after being right time and again, only for a louder male voice speaking past her.

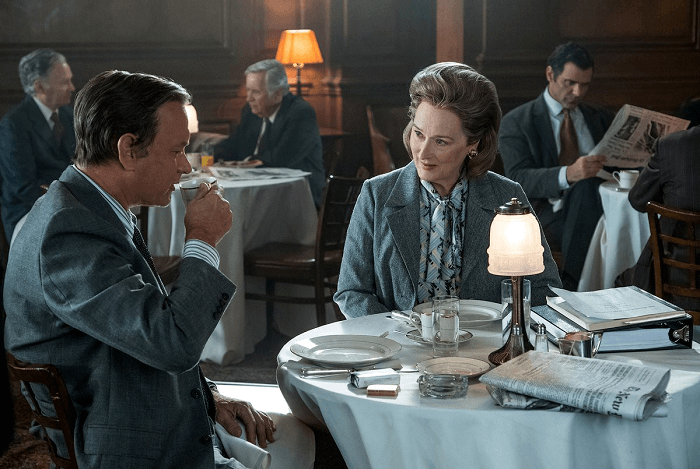

Streep plays opposite Tom Hanks as the garish editor-in-chief, Ben Bradlee. Bradlee plays the brash angel on her shoulder, pushing her to charge forward towards publication regardless of consequence. His calling is to honor of the sanctity of the press, a lesson he learned himself as he separated himself from the political elite – a task he urges Katharine to undertake. The moral weight of his argument begins as soon as the movie’s opening scene where, following a brutal ambush, a former soldier is seen behind a typewriter, and giving honest council to the Secretary of State about their lack of progress in Vietnam. From jump, Spielberg’s camera angles of the typewriters and printing presses assert the real weapons of this war, the pen as its sword.

As stakes are based on the decision to do the right thing, tension comes from increasingly significant motives to do the opposite. The initial conflict is the struggling Washington Post trying to keep up with the thriving New York Times, the paper always one step ahead of them in investigative reporting. Next, there’s the threat of Katherine losing the company and failing her family’s business if banks pulled out of their purchasing deal when the government inevitably targets the Post for their reporting. An injunction had already silenced the New York Times – eventually leading to the Supreme Court case New York Times v. United States – and Katherine’s business would not survive if her advisors were to be believed. Stakes are raised highest when the Post’s source is implicated in Nixon’s injunction, the first of its kind from the president of the United States, which could result in going to prison if the Supreme Court ruled against them. A failed company and fall from the DC high-culture establishment is one thing, going to prison for espionage and treason is quite another for “doing the right thing.” By then the stage is set with the magnitude and crux of the film’s message in place: this isn’t just about the Washington Post versus the government. This will shape the entire future of journalism.

This, of course, all leads to Streep’s moment of decision that is beautifully strong in its vulnerability. Katharine does not make a speech, or a triumphant declaration, or a one-line haymaker, or a quotable catchphrase that captures the force of the moment. It’s a stumbling mutter that struggles from her lungs and out her throat that carries the same magnitude. Again, it’s a non-spoiler that The Washington Post made such a decision, but its potency came from the right thing being done with such convincing uncertainty, so much that you wonder, if only for a moment, what loss could have been.

The Post ultimately ends with a nod to Watergate, and as we look to our present – what comedian and host John Oliver calls “Stupid Watergate,” The Post reminds us the weight of the historic moment we are in. Retelling of the Supreme Court’s decision in a crowded newsroom of people, the message was meant to remind us all: the press is meant to “serve the governed, not the governors.” And to that end, The Post is wonderfully successful.

Are you following Black Nerd Problems on Twitter, Facebook,Instagram, Tumblr, YouTube and Google+?

Show Comments