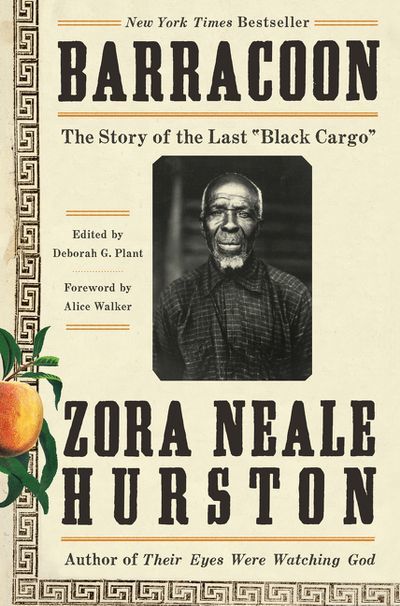

When you sit down to read a book like Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo, you know that you are about to bear witness. If you’re like me, you might feel that doing so is both an obligation and a privilege. In a world that so often tells us that we imagine the slights against us — that slavery was abolished so long ago as to be irrelevant; and that we must look forward, not back — it’s vital that we access the history still available to us. Equally important is that we value our history and our historians. What Zora Neale Hurston did in recording Cudjo Lewis’s story is a reminder that if a light is to be shone upon our ancestors, best that we be the ones holding the light.

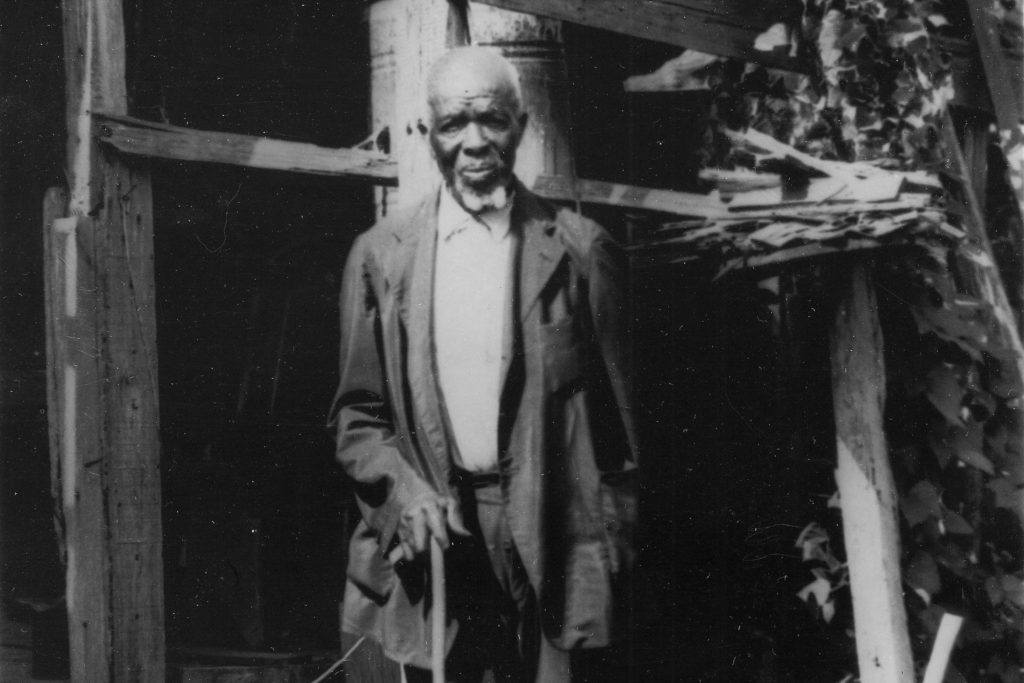

A slave narrative in the tradition of those recorded by the Federal Writers’ Project in the 1930s might focus solely on the experience of Cudjo Lewis (known also as Kossola). Hurston’s extensive interviews, which spanned over two months, do more. They paint a picture of a life derailed and rebuilt as best as possible.

The tale of Cudjo’s life begins in his beloved Africa. He tells us, through Hurston, about tribal warfare and rites of adulthood. Ultimately, his story details how he came to be enslaved and shipped to America on the last known slave ship, the Clotilda.

All these words from the seller, but not one word from the sold.

Brought over so close to the end of the Civil war, Lewis was not born — nor would he die — as an enslaved person. His recollections act as a bridge between Africa and America, somewhat encapsulating how a hyphen was wedged between these two places, naming a people as of and from both.

Bored by the familiarity of “… but Africans sold other Africans into slavery!” arguments, I was relieved at the nuance communicated in the telling and writing. The creation of a market that deals in violence is and always has been a violence unto itself. Cudjo’s telling makes that act of violence unavoidable.

Lewis recounts how tribal kings were spurred into unprovoked wars. This allowed for the capture and sale of prisoners of war, to feed the unconscionable and insatiable appetite for black bodies to enslave. Lewis’s notoriety is as one such spoil of war, sold into slavery by a neighboring and greedy tribe.

This is not a slave narrative, however; it is the story of a man who was enslaved and then freed by an Amendment. Cudjo’s life after enslavement is as fraught as so many other Reconstruction stories. Where Hurston excels is the apparent authenticity of the rendering. At times, it feels as though you are hear Cudjo speak: “Derefo’, you unnerstand me, it one day not long after dey tell me to speakee for lan’ so we buildee our houses,” he says of his and his fellow Africans desire to build a home of their own in America. The dream of returning to Africa had revealed itself to be just that — a dream.

This is the part of the book that made this review hard to write. In fact, I’ve sat with this half-written review for months. Thinking occasionally about the book, but most often about my grandfather.

If Cudjo was a man stuck between two worlds and stranded in the not exactly laissez-faire Reconstruction (violence is never hands-off), then so too was my grandfather stuck between his brilliance and the limitations put on it by Jim Crow.

This didn’t hit me at first. As I read, there was simply an echo. I read a lot of slave narratives and so I brushed it off as a familiarity of voice, of story. As I read on, I found myself thinking more and more of my grandfather. I didn’t realize that these seemingly random thoughts were connected to the text.

I read on, and after I finished, it became obvious that I couldn’t think about the book without my grandfather’s presence in my thoughts. It was, in part, Cudjo’s storytelling. He made all the points he needed to with a story from his youth. Even now, I can hear my grandfather, his voice solemn and deep, telling me about Alabama and his people, the land he was from, and how he came to be in the North as a man. I can hear his belly laugh as he recounted the troubles he got into as a barefoot boy even now.

“I want to look lak I in Affica, ’cause dat where I want to be”

It makes sense in retrospect that I connected with Cudjo’s story through my grandfather’s. Both men bore the repeated tragedies of this life with resilience and weariness. American was a lie and a disappointment to them both. Trapped inside a system designed to keep them under its heel, they chafed and found the best ways they could to thrive to the extent possible.

Finishing Cudjo’s story, I asked myself what he might have been if he was never caught in the fangs of slave trade. What might he and other enslaved people like him achieved, were they not just turned out into the world with no money or land? It makes sense that I could never read this book without thinking of my grandfather. Those questions are the ones that haunt me. The life he built out of what he could, relatively speaking, was good. What might he have been or accomplished if he were not thwarted in his pursuit of excellence by America’s specific brand of racism?

Obviously I’ll never know, yet I’m glad that the recently published Hurston text forced readers to reexamine the aftermath of slavery through the context of era-specific narratives. Cudjo’s unique position in time makes his story as American as they come. Barracoon forwards he conversations we need to be having in terms of race, reparations, and legacies.

Show Comments