You aren’t supposed to judge a book by its cover, but as I gawped at the umber-and-ebonied hued illustrations of a black man and a black woman—him lordlike and corded with reams of burnished muscles, her drawn with doe-like grace and a crowning afro-puff hairdo—posed against the misty backdrop of megalithic edifices evocative of a magnificent medieval African nation, I couldn’t have disagreed more with that adage. I knew that this book would blow my mind. This book would decolonize my imagination, which had been overrun with images of straight-haired, Caucasian elves, wizards, and monarchs. This book would be one of the best I’d ever read. I was right.

It’s been a couple of years since I checked out my local library’s sole copy of Imaro 2: The Quest for Cush by Charles R. Saunders. Since then, black monarchs have ascended the thrones of popular culture, from movie screens to Barnes & Noble bookshelves. It seems that audiences were hungry, starved even, for African fantasy heroes and heroines. And while such social awareness surrounding fantasy stories featuring black people is new, the stories aren’t.

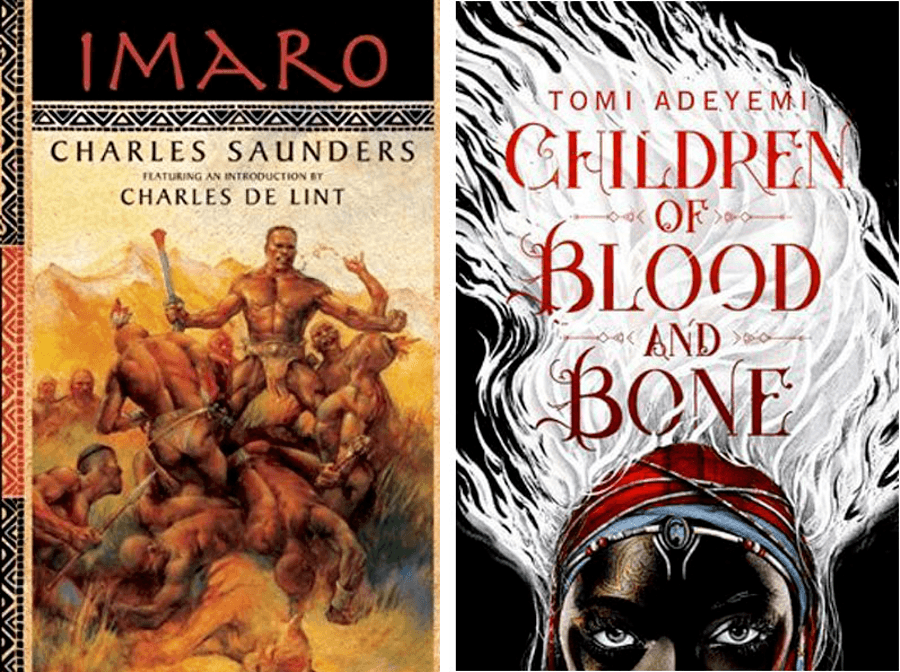

Tomi Adeyemi’s bestselling YA novel Children of Blood and Bone represents this dichotomy of once-niche stories becoming mainstream. Through melding African cultural elements and political allegory in CoB&B, Adeyemi fashioned a story that is just as much the “next Harry Potter” as it is a new entry in the canon of sword and soul, which was founded by fantasy writer Charles R. Saunders in the 1980’s.

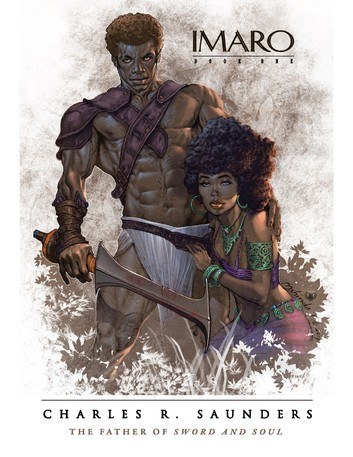

The Father of Sword and Soul

Originally from Elizabeth, Pennsylvania, Charles R. Saunders emigrated to Canada in 1969. Heroic fantasy literature intrigued Saunders because he saw popular stories about sword-wielding, barbarian heroes and warrior heroines as cultural derivatives of ancient mythological characters. But, while most heroic fantasy authors wrote stories based on European culture and mythology (e.g., J. R. R. Tolkien, J. K. Rowling, and George R. R. Martin), Saunders was inspired by pre-colonial African history, mythology, folklore, and legends. His Afrocentric interests, together with his enthusiasm for Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian, led to the birth of one of his most iconic characters: the Ilyassai warrior Imaro. With Imaro, Saunders created a subset of the fantasy subgenre sword and sorcery, which he described as “sword and soul.”

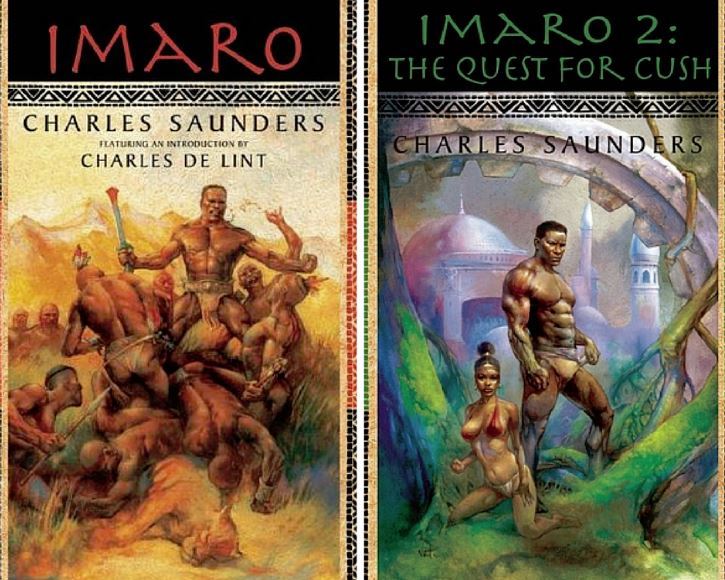

Saunder’s Imaro (published in 1981) was his debut novel and the first installment in a four-book series. In 1982, Imaro was nominated for the Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy Award. Like the West African-inspired land of Orïsha in Adeyemi’s CoB&B, Imaro takes place in the fantasy African world of Nyumbani. There, the hero battles foes both human and supernatural. Though the world of Imaro is based off Saunders’ meticulous research, the titular character is not the fantastical reimagination of an actual figure from pre-colonial African history or lore. “Imaro,” Saunders explained in a 1984 interview “came out of my own head. I think he was born when I watched a Tarzan movie and fantasized a black man jumping up and beating the hell out of Johnny Weismuller. Eventually, that man became Imaro.” For Saunders, the character of Imaro was a revisionist statement in fantasy fiction. As he told micro-press publisher Innsmouth Free Press in an interview, “I always saw Imaro as the guy who could reclaim the Africa-of-the imagination from Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan and other white jungle lords … I believe [Imaro] constituted a breakthrough in fantasy. He opened readers’ eyes to the possibility of a different way to portray Africa and Africans in the genre.” Through Imaro and later Dossouye—the chronicle of a sword-wielding, war-bull-riding soldier from an all-female military unit set in the kingdom of Abomey—Saunders shone a light on what Eurocentric society derided as the “Dark Continent.” He displayed the kaleidoscopic glory of African civilization in the bustling cities and characters of his sword and soul fantasy novels.

Adeyemi also envisions CoB&B as a challenge to fantasy fiction that is majority white, and to its racist readers who vehemently maintain that such a lack of diversity is the default of the genre. Protagonist Zélie was the product not only of Adeyemi’s fascination with West African gods and goddesses, but also her drive to create characters that both empowered and expanded readers’ imaginations of who could be a hero or heroine. “That was the dream,” she said in one of her interviews on her mission in writing CoB&B. “…that it would be so good and so black and so dark. Not just black, but featuring dark-skinned black people in a way that questions Hollywood’s image of what black people must be and look like.” Like Imaro and Dossouye before her, Zélie, Amari, and Tzain are revisionist images within a majority-white genre that regularly marginalizes people of color.

An Allegory for the Black Experience

While Saunders based the locales and protagonists in his sword and soul novels on pre-colonial African kingdoms and mythology, he also drew on the African-American experience to create terrifyingly realistic fantasy villains and sorcery. According to fantasy writer Milton J. Davis, who Saunders describes as his “sword-and-soul-brother,” Imaro was as much reflective of the black experience with racism during the late 20th century as it was steeped in 15th-century African history. That political allegory is uniquely embodied by the evil Mizungus, the pale-skinned enemies who Imaro faces in the first chapter of The Quest for Cush (which was first published as a short story entitled “City of Madness” in 1974).The Mizungus (Swahili for “white people”) traveled from their home island continent of Atlan to invade Nyumbani centuries before the events that take place in the Imaro series. Deceived by demon gods into believing that the people of Nyumbani were subhuman, the Mizungus enslaved the Nyumbanis and sent both captives and the land’s rich resources back to Atlan on slave ships. And if these characters’ parallels to colonizers and slavers were not enough, Saunders also invented a derogatory term they used to describe the great people of Nyumbani: nagas, or “despised ones.” Through the Mizungus, Saunders created a fantasy world in which his protagonists must confront and ultimately overcome hatred and violence. His allegories to slavery, colonialism, and racism do not compromise the action-adventure or narrative elements of his Imaro novels, but rather serve to elevate and enhance the fantasy storylines by making them realistic and thus relevant.

With CoB&B, Adeyemi evolves the sword and soul genre through allegorizing the black experience with police brutality. Her book has even been appropriately described as a “Black Lives Matter-inspired fantasy novel.” One particularly scene in which a thirteen-year-old divîner, or one who has the potential to do magic, but isn’t yet a fully-fledged maji, is shot and killed by an archer in the king’s royal guard is representative of black children who were shot and killed by police in real life. (Adeyemi discusses this in her Author’s Note.) Like Saunders did with his Imaro novels, Adeyemi also made her main characters in CoB&B face real world experiences, like violence and the dehumanization of black bodies, in a thrilling, deceptively fantasy environment.

The Problem with Using ‘Black’ as a Modifier

It is important to recognize Adeyemi’s CoB&B as another megastar in the sword and soul universe created by Charles R. Saunders because it demonstrates that today’s Afrocentric epic fantasy stories are not only the “black” versions of fantasy stories by white authors, but also entries in their own genre. Reviewers understandably hashtag book jacket synopses in order to encapsulate 500 plus-page novels in a handful of characters. And calling CoB&B the black Harry Potter speaks to how Adeyemi created a world that is as visually arresting, influential, and momentous for readers as the one created by J. K. Rowling. But, by solely describing fantasy novels by contemporary black authors as being the black versions of fantasy stories by white authors, critics are unfortunately New World-ing a subset of genre fiction that pre-existed them. The “black” modifier has also carried over to adult fantasy fiction. For instance, Man Booker Prize-winner Marlon James’ upcoming fantasy novel Black Leopard, Red Wolf is being called the African “Game of Thrones” and described as a tale that is “‘unlike anything that’s come before it.’” And yet, as Adeyemi has stated, “We’ve always been writing these stories.” Exclusively comparing black fantasy authors to white ones though, obscures that history.

Re-categorizing African-inspired fantasy novels as sword and soul tales would also make it easier to find authors writing similar Afrocentric stories. Authors like Milton J. Davis, who has written several sword and soul epics as well as coedited the anthologies Griots: A Sword and Soul Anthology and Griot: Sisters of the Spear, with Charles R. Saunders. Authors like Carole McDonnell, or Troy L. Wiggins, or Phenderson Djèlí Clark (whose debut novella The Black God’s Drums came out this year), or Balogun Ojetade. ‘Sword and soul’ provides umbrella terminology to identify Afrocentric fantasy stories and prevents depending on generalized comparisons to describe a story that connects precolonial African culture and history with contemporaneous political allegory. There are a number of current and upcoming projects across various mediums that could be categorized as sword and soul, like YouNeek Studio’s historical fantasy graphic novel (and soon-to-be animated series) Malika, about a titular character inspired by 15th-century African warrior queens, or Disney’s African princess fairytale movie Sade, which will be set in a fantasy African kingdom.

Before Malika and Sade, Charles Saunders imagined Imaro as being the first of a new kind of hero. “Currently,” he told an interviewer in 1984, “90% of the fantasy on the bookshelves is based on 10% of the world’s epic mythological traditions. I hope more attention will be paid to that untapped 90%.” (In keeping with that hope, Saunders published his newest collection of short stories, titled Nyumbani Tales, last year). And though the road from Nyumbani in 1981 to Orïsha in 2018 was long, I think that sword and soul has at last arrived in mainstream movies, graphic novels, and epic fantasies like CoB&B. The only thing new about these stories is that they’re finally getting the attention, financial backing, and praise they’ve always deserved. Nyumbani forever!

See more of guest writer Melissa Grace Burlock here on her twitter.

© 2018 by Melissa Grace Burlock.

Want to get Black Nerd Problems updates sent directly to you? Sign up here!

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook,Instagram, Tumblr, YouTube and Google+?

Show Comments