Manga is singlehandedly causing the downfall of Japanese society, and CNN, for one, is very concerned about this disturbing trend.

All sarcasm aside, in an article that was published on CNN last week called “Sexually explicit Japan manga evades new laws on child pornography,” the news site went into the passage of a law in Japan that says people caught with child pornography will either be sent to jail for a year or slapped with some heavy fines of up to $10,000. OK, cool. Kiddie porn is bad and creepy pedos who exploit children should be punished—as it should be.

[divider type=”space_thin”]

But the article focuses on hentai, questioning whether it should be banned along with kiddie porn and implying that it may be related to child abuse (though it repeatedly says no link has been made between anime/manga and child abuse, it continues to cite statistics that seem to link the two).

CNN quotes Liberal Democratic Party member Masatada Tsuchiya as saying hentai “is not protected under freedom of expression.” Let me take a second to say that there are plenty of manga/anime tropes that I’m personally uncomfortable with, and while I don’t necessarily agree with the concepts behind some of this artwork, I believe in freedom of expression nevertheless.

[divider type=”space_thin”]

Besides, I could say that I have this same feeling about many American movies and magazines and works of art. Western culture, despite its cocky, self-righteous belief in its own openness and comparative liberalness, can only claim such a belief in specific areas of interest related to its own culture. If an American film is released depicting children having sex (through the use of body doubles or whatever other techniques to circumnavigate the illegality of kiddie porn—but the implication/concept is there all the same) or if a super hip work of art depicts some other illegal sex act such as bestiality or incest or if a popular TV show depicts rape, torture and gory acts of violence, many of us don’t bat an eye, but rather whip out some discourse about entertainment media, free expression and the First Amendment. But when it comes to another culture and another art form that is a bit unfamiliar, then it becomes something way more perverse.

But the problem, it seems, is specifically the children, which I completely understand, CNN. I do. I definitely don’t condone the exploitation of children and the dissemination of materials that support such acts. But the fact is—one that CNN pretty much glazes over in its undercover black op into the dark world of otaku (yup, they went in with secret cameras, because that’s totally necessary)—that these are drawings. They’re not real pictures. They are art.

Yes, I said art. I know, I know, you may be loath to call this work art, but art is a broad term open to interpretation, and the fact of the matter is that the art of manga/anime is a seminal part of what they are. (By definition, as it is stated in the article, manga means “casual drawing.”)

But even if we consider them works of art, they’re still obscene and should be banned, right? Even if we gloss over the essential American idea of freedom of expression, we’re still left with a whole history of artwork that has been obscene and disturbing and inappropriate at times. Have you visited an art museum lately? Check out those Romantic numbers, the Baroque art—whole eras of art depicting scenes of nudity and sex. How many of those bring to canvas scenes taken from myths, many of which describe instances of obscene, “unnatural” sex and violence? And what about modern art? Take a trip to the Museum of Modern Art, where you will most definitely see art that may make you cringe or blush. While many of these works of art have been banned or censored in the past, a lot of what could be called obscene art still lives in our museums and on our newsstands and gets produced into popular TV shows and movies. Why? Because we as consumers are expected to be able to tell the difference between fact and fiction, between real life and an illustration.

[divider type=”space_thin”]

[divider type=”space_thin”]

And doesn’t this point sound familiar? I must make an admission here: Earlier, when I said how many Americans fail to judge our violence- and sex-saturated media with the same strictness as we judge the controversial trends in other cultures, I made an omission. In the last two decades or so, a trend occurred in which a number of video games and TV shows became the target of Americans who claimed the media was negatively affecting people, particularly troubled, impressionable children who may be then tempted to act on their violent impulses. The little bit of fire behind those arguments quickly simmered out, in part because cultural phenomena—such as the epidemic of school shootings in America in recent years and child abuse in Japan—are very rarely, if ever, symptomatic of one singular product, especially not something like “Grand Theft Auto” or whatever brand of suggestive artwork you can find in bookstores. Surely they can be influential, but to say it’s as simple a cause and effect relationship as CNN implies is the case with hentai and child abuse ignorantly overlooks the more influential societal institutions related to these ills. So how about we stop threatening our cherished belief in freedom of expression by planning to ban some controversial material and instead focus on the issues themselves?

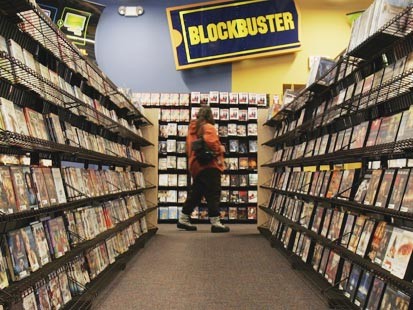

Oh, and CNN is so shocked that you can buy hentai in Japanese bookstores, which is ironic because we come from a culture so openly obsessed with sex that we’re saturated with nudity and sex in our ads, TV shows, video games, movies and art. We have erotica and “Playboy” in our bookstores. Before video rental stores became obsolete, we used to have shelves upon shelves of pornos in our Blockbusters and Hollywood Videos.

[divider type=”space_thin”]

Thankfully, CNN manages to quote Mio Bryce, who the news site calls an “expert on anime and manga from Macquarie University in Sydney,” in saying that only a small percentage of the anime/manga industry contains this kind of explicit material. In one of the few statements I wholeheartedly support in the piece, Bryce says, “Very often people think manga equals sexual or manga equals violence. But it’s only a part of manga … there are some very poetic, very beautiful ones.”

However, at the conclusion of the piece, CNN draws on Bryce’s claim that “cuteness is the problem,” that the Japanese obsession with “kawaii” and “Lolita” culture “makes you feel you have to protect the person, and there’s a very fine line between ‘I can protect the person’ and ‘I can control the person.'” Even if we look past the sheer ridiculousness of the sentence “Cuteness is the problem,” we still run into a problem of misplaced blame and the belief in another cause and effect relationship that doesn’t actually exist. Lolita fashion and culture—despite its name, which many people relate to the story of the famous Nabokov novel—is not meant to be about sexually ambitious young girls who are prey to pedophiles. It’s like when American girls are vilified and shamed for wearing sexy or suggestive or even plain flattering clothes and told they are “asking for it”—whatever crime or misdeed “it” is. Sexuality does not automatically warrant sex or abuse, in the same way “cuteness” does not automatically warrant sex or abuse. To say these factors cause these results is to understate the accountability of the actual culprits—the abusers.

[divider type=”space_thin”]

So CNN, before you embark on your next undercover mission and conduct your “research” for what I’m sure you consider unbiased journalism, maybe you should look for the real story.

Show Comments