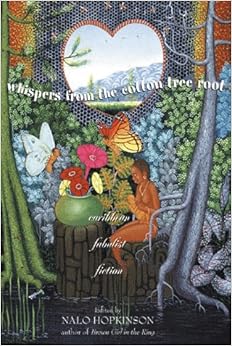

About 5 years ago, I was in my local science fiction paperback book store, now closed, when I found Whispers from the Cotton Tree Root while looking for something else. The subtitle “Caribbean fabulist fiction” was enough to grab my interest, and Nalo Hopkinson’s name on the spine had already guaranteed I’d buy the book. Then I saw this:

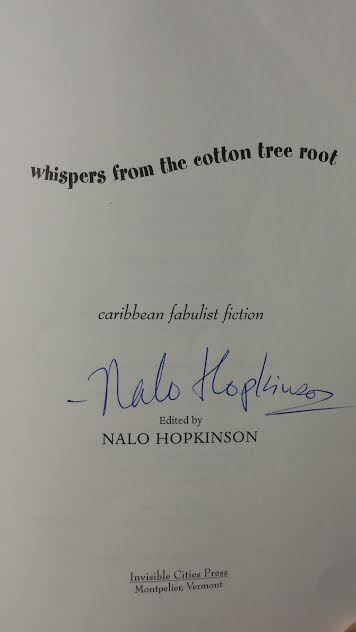

OH YEAH, SIGNED COPY! I was stoked. I quickly devoured the first few stories, then let life take me away while the book rested on the shelf patiently. This summer, as part of my Summer Reading List, I returned to it, and I’m glad I did. As Hopkinson says in the Foreword, these stories “invoke a sense of fable. Sometimes they are fantastical, sometimes absurd, satirical, magical, or allegorical.”

As I read them, I was struck by how many wouldn’t be considered “science fiction” or “fantasy” by more genre-bound readers. At the same time, by stretching the boundaries of what counts as science fiction/fantasy, they speak directly to me as a Black reader who is looking for something more. The genre police use “the usual” to avoid interrogating why something is “usual.” These stories refuse to be just one thing, embracing a both/and philosophy and demonstrating how much fun fiction can be that centers the rest of us and our ways of storytelling.

At around 300 pages printed (I’m so old school), the book is split into seven sections with subtitles like “‘Membah” and “The Broad Dutty Water.” The vernacular of the Caribbean is diffused through most of the stories. Sometimes it is so thick I had to read the story out loud to get the pacing right, but the language is welcoming as well as indicative of difference. For example, in the first story “Ida” the narrator is older and physically disabled from birth. She’s been confined to a nursing home where she weaves her own tale with that of the ghosts of slaves in her homeland, her whole point being that people like her, who have lived at the margins, are often best equipped to hear the stories that persist all around us.

Those stories, history itself, is at the core of all of the short stories, sometimes explicitly, as in “Just a Lark (or the Crypt of Matthew Ashdown).” Told in a purposely Lovecraftian-style, which comes with its own political implications, this tale is one of a dilettante White man of the planter class struggling to place himself between his island’s brutal history of slavery and repression and the growing independence movement of the post-World War II era. It is a well-put together story that works on the level of reality, horror, magic, and politics.

It contrasts with “My Mother” by Jamaica Kincaid. Kincaid is one of the great queens of Black/Caribbean fiction. Her story in the anthology builds on her lifelong meditations on her relationship with her mother, but makes that meditation extended and strange. I finished the story feeling like a transformation had happened, that the daughter had come to understand her mother by becoming her, both magically and physically. The story, like many others, challenges the reader to recall their own context and bring it to the story, using that shared context to come to understanding.

One of the most “science fiction” of the stories is “Once on the Shores of the Stream Senegambia.” It fits well in the traditional science fiction genre because of its futuristic setting and its biotechnological premise. The story depends on the reveal at the end, so I don’t want to give too much away, but it is a woman’s story, built on her relationship with another woman, Drew, and a growing understanding that her own senses can’t be trusted. The tale is complicated, and slightly creepy in its implications. It recalls many other science fiction short stories I’ve read, with the difference that this one doesn’t erase the specific overlapping identities of the narrator, but highlights them.

Not all of the stories are dark or serious. One, “Uncle Obadiah and the Alien,” is a great story full of Rasta jokes and anti-colonial snark. Basically, an alien crashes in Uncle Obadiah’s “herb” patch. While this destroys his product it does allow him an opportunity to converse with a fellow follower of the great Haile Selassie, whose fame has spread throughout the galaxy. It ends with this joke. When asked when the aliens and the Rastas will be re-united, the alien says:

“… no one should return until all Africans have been reunited and all nations of Earth accept his Imperial Majesty as its rightful ruler.”

I wave good-bye because I know me wouldn’t see him again.

The anthology ends where it begins, in dreams and memories. “My Funny Valentine” is one of the most experimental short stories in the anthology, straining the difference between fiction and poetry and playing with type and symbol to bring across meaning. “Devil Beads,” the last story, is a fitting ending in which the youth lead the rest of us forward into all the possibilities that the future holds.

In Whispers from the Cotton Tree Root, Hopkinson pulled together a wide-ranging survey of Caribbean fiction, showing what connections can be made when we expand our definitions — we can be inspired, enlightened, and amazed. I enjoyed this anthology and can recommend it to any reader looking to become more familiar with genre-bending fiction from the Caribbean. As Hopkinson says:

“Read it in the spirit of breaking the rules.”

Are you following Black Nerd Problems on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr or Google+?

Show Comments