*Puts on fake pretentious academic film Blerd hat* Nope feels like Jordan Peele’s departure from referential Black symbolism and entry into contemporary Black existentialism. Or a precise mix of both. Or neither. *Removes fake pretentious element* It gives us another layer of Peele’s view of the world. Where Get Out was a story about how racism plays out and where Us examines what the Black condition is in relation to trauma; Nope puts a lens on the role of Black erasure. Not just the historical machinations behind said erasure, but the role knowing the erasure happened plays in motivating non-whites to persevere and make a name for themselves against all odds. *Takes film Blerd hat off and replaces with sad boy Blerd hat*

It’s a jarring and sober reminder to remember that the United States is a broken country built on broken promises and sustained by selling broken dreams. Especially when there are so many creature comforts to hold our attention from those very real conditions. The divide in this country is so intense that it feels physical. There has never been a reconciliation for the dissonance that the ‘land of the free’ has never been that. At all. Ever. You can see it in all aspects of American society. That lingering feeling of dread is why race-based horror has always been a hit. For reference, movies like Tales From The Hood, Bones, His House, Tales From The Crypt: Demon Knight, Vampires Vs. The Bronx and the first and last entries of Candyman all fall under the umbrella of race-based horror. Whether they are a box office smash, a new Criterion entry, a sleeper hit, or a cult classic – the genre always makes waves. The reality is, as long as there are divisive race politics at play in the places these films are made, there will always be a place for this kind of horror.

Wild enough, even James Baldwin weighed in on this dynamic. When The Exorcist dropped in 1976, he wrote a piece in response titled “The Devil Finds Work.” Wherein Baldwin implies that because white audiences rarely experience genuine fear in their daily lives, horror thrives as a film genre. Going to see fear in a controlled environment is fun in that way. There’s a distance, a resolution. Unlike the daily list of recurring fears that are normalized in the Black experience. So, when Black creatives explore horror (the fearful), what they really do is transmute terror (the traumatic) into something digestible for those who do not experience it.

Where earlier race-based horror pieces shifted, shook, or shattered stereotypes for acceptance; newer entries investigate the true monsters: the ones who made the stereotypes. Take Peele’s Get Out, which forces white audiences to confront how they are complicit in racism, especially when they believe they are not. Or Nia DaCosta’s Candyman, which cites the elitism of the art world (vis-a-vis the white gaze) as a catalyst for gentrification and displacement in Black and Brown communities. All of which is to say, there’s enough injustice, violence, inequity, and dehumanization in American society to fuel the horror genre in perpetuity.

Nope enters the race-based ‘horror’ conversation in a far more understated way: erasure. If you erase the contributions of Black people from history, does that change the value of Black people in the future? By exploring erasure, Peele addresses the devaluation of Black people across time. The true horror of Nope is in the postulate. Can we exist in a future where we have no history? The true terror is in the ways it recounts how excluded Black people are from American history (a surprise to no one keeping track of the political debates around critical race theory). Black ‘cowboys’, Black farmers, Black animal wranglers, Black stunt people, Black actors, Black filmmakers. Each one of these is addressed in some form or another in Nope. One clever turn in Nope examines a lingering question; what do Black people have to do to get credit for the ingenuity we’ve cultivated to survive systemic racism and disenfranchisement?

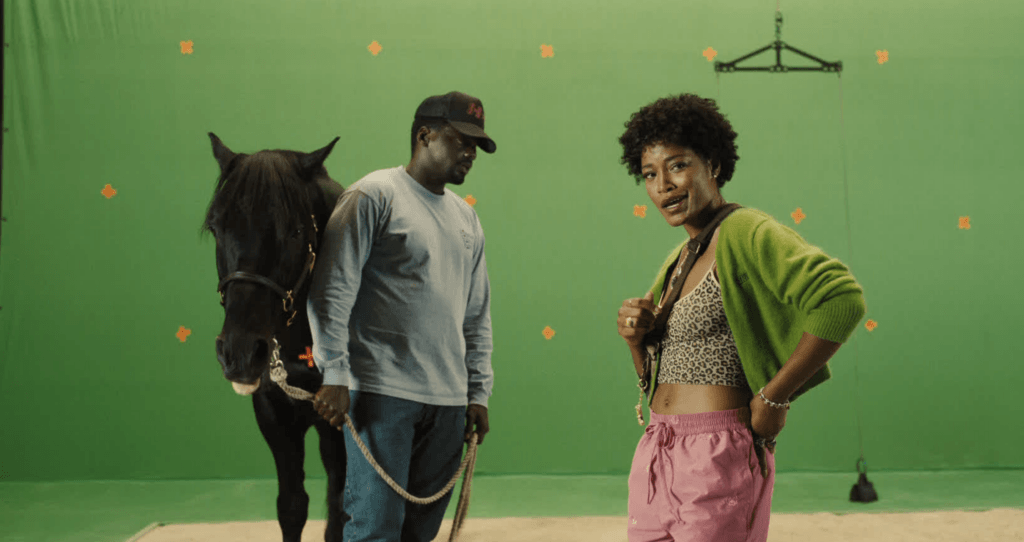

We get to see that question play out with on-point performances from the whole cast. The gravitas and interplay between real-life erasure and fictional references to it go off in Nope. Keke Palmer’s range is on full display as the energetic Emerald Haywood and it plays perfectly off of Daniel Kaluuya’s understated intensity as OJ Haywood. Kaluuya and Palmer could be the only two cast members and this movie would be damn good. Steven Yeun and Brandon Perea round out the main cast and bookend the ‘awkward and strange’ element that is Peele’s lifeblood. We are blessed with turns from Keith David and Michael Wincott that just elevate the movie in the best ways possible. [Note: Peak Blerd imagery was achieved with Keke doing the Kaneda motorbike slide from Akira (which Peele was once attached to direct the live-action adaptation of)!]

With little to none of the cryptic symbolism of Us or the overt microaggressions of Get Out, Nope is a lean thriller with horror pacing and a sci-fi twist that sees Peele finding his stride. Audiences well-versed in Peele’s subtextual subject matter will definitely rock with it. Folks brand new to his work will be enthralled by this genre-flexing movie that will leave a memorable mark on something they thought they knew so well. Nope is a streamlined and focused film that looks cut and dry on the surface but digs into deep sociopolitical territory without ever letting you know. Unless you’re Black, then you might know. The rub with Nope is the same as the very thing that sets it apart from the rest of Peele’s work. It is not exact in anything but the main plot, which means there’s so much a viewer can “read” from it. The number of things I interpreted from this movie could fill a soon-to-be-banned high school history book. That said, Nope is a well-made movie that will land differently with every viewer and have you looking at the skies a little differently.

Want to get Black Nerd Problems updates sent directly to you? Sign up here! Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Youtube, and Instagram!

Show Comments